Memorials

2025

Gregory Nusinovich

Dr. Nusinovich was an official member of our IRMMW-THz conference International Organizing Committee from 2004 through to 2009 and an active participant in the conference series going back much further. He received the Kenneth J Button award in 2012 for his many contributions to the field of gyrotrons and high-power sources. Gregory passed away on Dec. 11th. A short obituary can be found here:

https://www.dignitymemorial.com/obituaries/silver-spring-md/gregory-nusinovich-12664611

Jeffrey Hesler

Chief Technology Officer of Virginia Diodes and THz Pioneer

Jeffrey passed away on Saturday, October 18, 2025. While we are wait to post something more substantial from some of Jeffrey’s colleagues, a short obituary can be found here: https://www.legacy.com/us/obituaries/dailyprogress/name/jeffrey-hesler-obituary?id=59883010

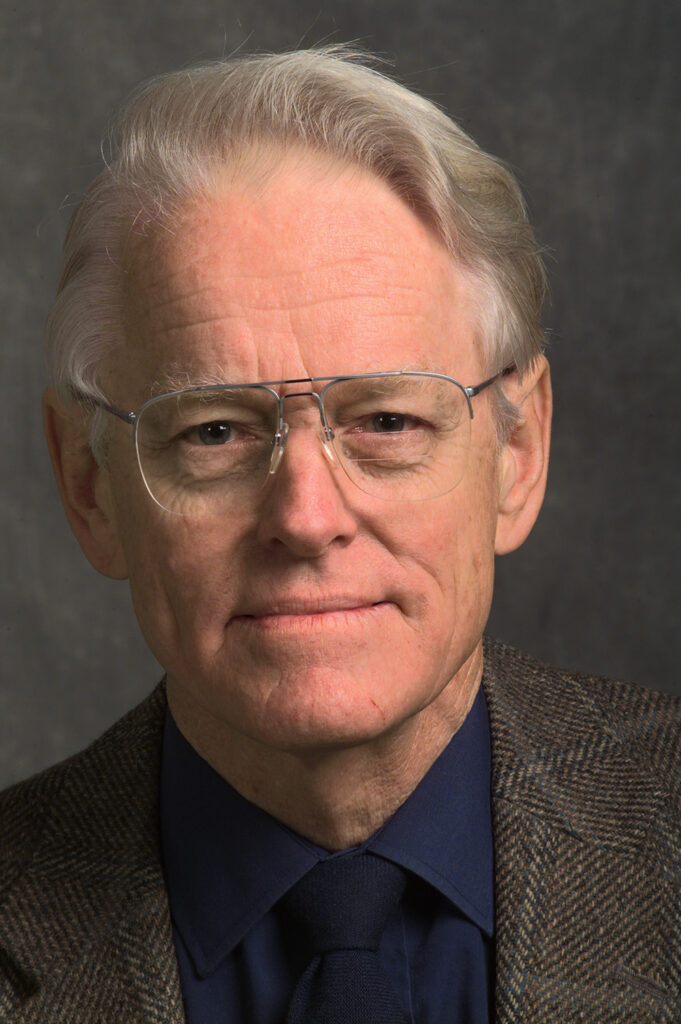

Neville C. Luhmann

1943-2025

Above (left to right): Thijs de Graauw, Koji Mizuno, and Neville Luhmann at the 2018 IRMMW-THz conference in Nagoya, Japan.

Neville C. Luhmann, Jr., a Distinguished Professor at the University of California, Davis and a towering figure in the fields of plasma physics and vacuum electronics, passed away on September 5, 2025, at the age of 82. He was a beloved mentor, a visionary leader, and a world-renowned scientist whose work helped shape modern high-frequency electronics.

Dr. Luhmann began his illustrious academic journey at the University of California, Berkeley, where he earned a B.S. in Engineering Physics in 1966. He went on to receive his Ph.D. in Physics from the University of Maryland, College Park, in 1972. Following a postdoctoral research associate position at the prestigious Princeton University Plasma Physics Lab, he launched his academic career at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA).

Over a distinguished 20-year tenure at UCLA, he ascended from Assistant Professor to Full Professor. A natural leader and innovator, he founded and directed the Center for High Frequency Electronics and served as Co-Director of the Joint Services Electronics Program in Millimeter Wave Electronics. His exceptional ability to lead complex, multi-institutional research was recognized through his role as Program Director for several critical Department of Defense Multidisciplinary University Research Initiatives (MURI) consortia, focusing on high-energy microwave sources and vacuum electronics.

Dr. Luhmann joined UC Davis in 1993 and was appointed in 2003 to the position of Distinguished Professor at UC Davis, one of the highest honors bestowed upon a faculty member. He continued his groundbreaking work, co-directing the Davis Millimeter Wave Research Center and expanding his research into fusion plasma diagnostics. His international acclaim was evident through his roles as an ITER Scientist Fellow and his membership on academic committees for major international research institutions.

A prolific author of approximately 420 journal articles and 18 books, Dr. Luhmann’s contributions were celebrated with the most prestigious awards in his field. These included the Robert L. Woods/DoD Award, the IEEE John R. Pierce Award for Excellence in Vacuum Electronics, and the Kenneth J. Button Prize from The International Society of Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz Waves, 2005.

He was also a dedicated mentor, honored with UC Davis’s Distinguished Graduate and Postdoctoral Mentoring Award and the Consortium for Women and Research Outstanding Mentor Award. Professor Luhmann has supervised the graduation of more than 100 Ph.D. students, the majority of whom were women. Students and colleagues alike remember Dr. Luhmann for his unwavering support, intellectual generosity, and ability to inspire curiosity and excellence.

Dr. Luhmann was elected a Fellow of the American Physical Society and a Life Fellow of the Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers (IEEE), distinctions that reflect the profound and lasting impact of his work. He will be remembered for his brilliant mind, his generous mentorship, and his unwavering commitment to advancing human knowledge. His passing leaves a profound void in the scientific community, but his legacy will continue to illuminate the path for future generations of researchers.

Dr. Luhmann is survived by his wife, Janet Luhmann, and a wide circle of colleagues, students, and friends who will carry forward his legacy.

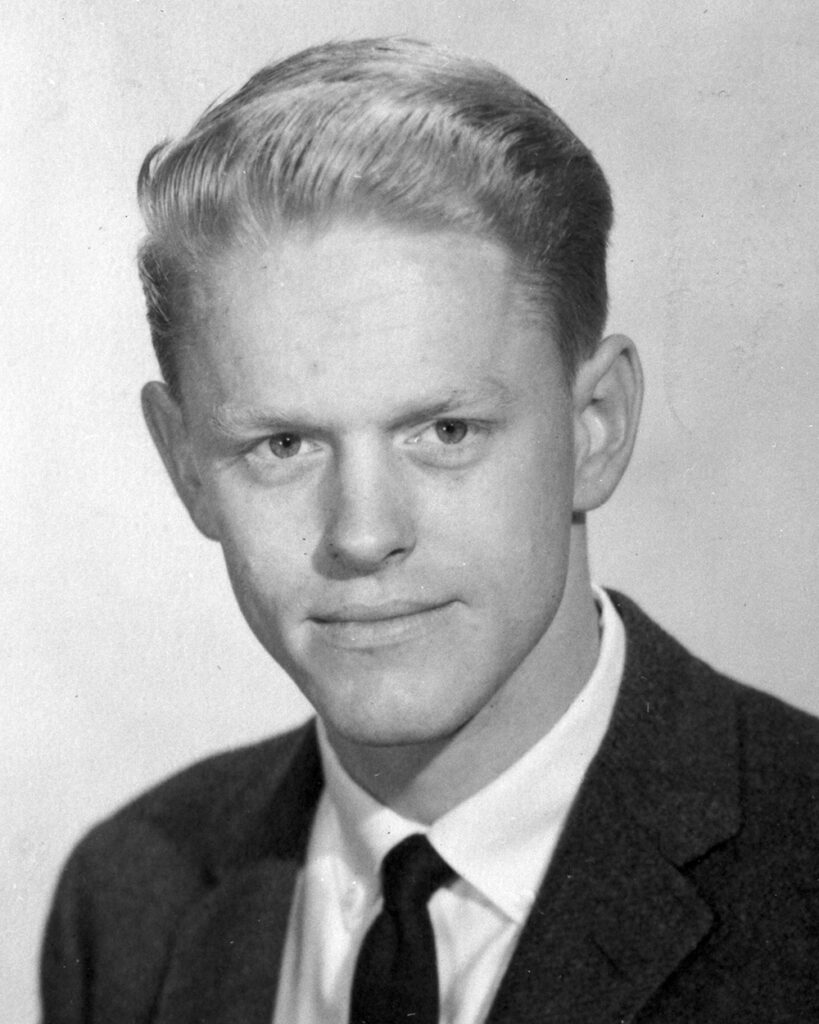

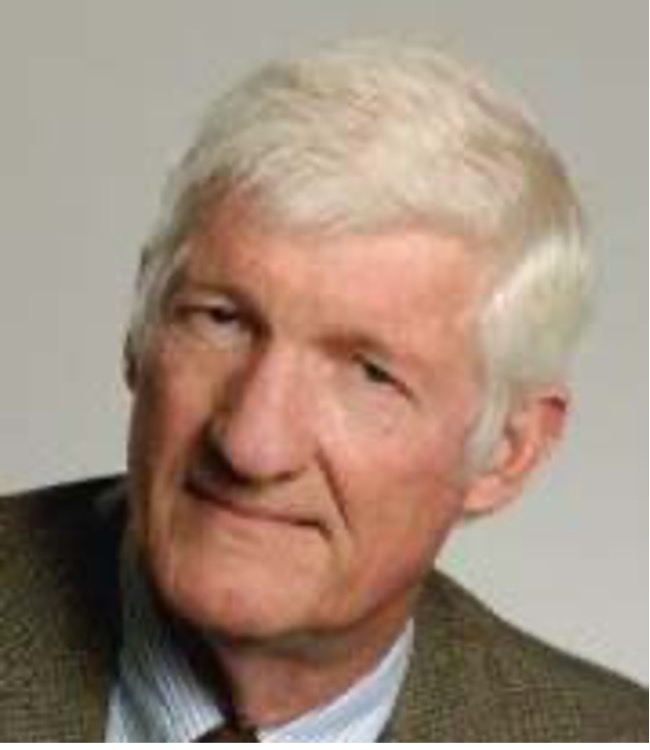

Paul Richards

1934-2024

The following was copied from: https://news.berkeley.edu/2024/09/25/physicist-paul-richards-a-pioneer-in-studies-of-the-cosmic-microwave-background-dies-at-90

FOR ADDITIONAL DETAILS ON PAUL RICHARDS’ LONG AND DISTINGUISHED CAREER, SEE: P. H. Siegel, “Terahertz Pioneer: Paul L. Richards,” in IEEE Transactions on Terahertz Science and Technology, vol. 1, no. 2, pp. 342-348, Nov. 2011.

Paul L. Richards, an experimental physicist who built some of the first highly sensitive detectors to probe the faint radiation left over from the birth of the universe, died peacefully at his home in Berkeley on Monday, Sept. 16. A professor emeritus of physics at the University of California, Berkeley, Richards was 90.

Richards got his start as a solid-state physicist, studying the properties of superconductors. But after the discovery of the cosmic microwave background (CMB) in 1965, he shifted to astrophysics and cosmology, employing instruments he had developed to measure the properties of very cold materials to also measure cold radiation from space. He built the first of these instruments — a Fabry Perot spectrometer — in the early 1970s with graduate student John Mather and postdoctoral fellow Michael Werner, who took it to a high peak in the White Mountains of California to measure the temperature of the radiation. Werner went on to the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena to lead the Spitzer Space Telescope as project scientist.

Richards’ second CMB instrument was much more powerful — a balloon-borne Fourier transform spectrometer that he built with Mather and graduate students David P. Woody and Norm Nishioka. They realized that only by getting the instrument above the atmosphere and cooling it with liquid helium would they be able to make truly precise measurements of the spectrum of the CMB. At the time, that meant balloon experiments from a launch site in Palestine, Texas. These and experiments by others provided strong support for the theory that the universe began with a Big Bang 13.6 billion years ago, with the cosmic background radiation the cool remnant of that very hot birth.

The details of the microwave background were so important to scientists because they provided “the initial conditions for astronomy” that grew into the galaxies, clusters of galaxies and large cosmic structures we see today, Richards told Science magazine in 1994. “If you want to know why there are big superclusters, why a great wall, why the deep surveys show these gigantic structures,” the answer lies in the details of the background radiation.

Mather later employed similar instruments aboard a satellite, the Cosmic Background Explorer (COBE). In 1992, COBE succeeded in detecting minute variations in the temperature across the sky, a finding Stephen Hawking called the greatest scientific discovery of the century. Mather and George Smoot, then at Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and now a UC Berkeley professor emeritus of physics, won the 2006 Nobel Prize in Physics “for their discovery of the blackbody form and anisotropy of the cosmic microwave background radiation.”

“Paul was my thesis adviser on the balloon project, which actually didn’t work right the first time, but became the idea for the Cosmic Background Explorer and my career at NASA,” said Mather, who after COBE took a position as senior project scientist for another highly successful project, the James Webb Space Telescope. “He was a brilliant mentor, a model human being and a great scientist. Paul’s a hero, and his ideas have grown immensely. The COBE mission came directly from his inspiration.”

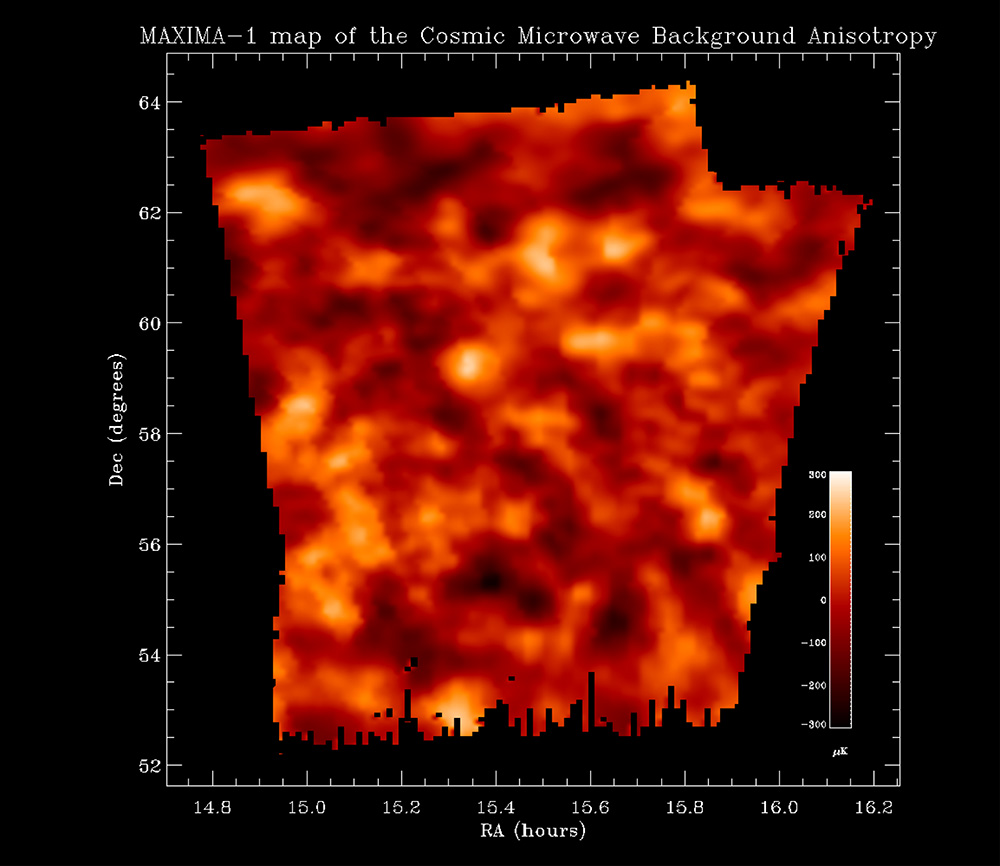

While COBE was under development, Richards began developing his own set of balloon experiments to probe the CMB’s spatial variation, or anistropy. The Millimeter Anistropy eXperiment (MAX) was the first of those, followed by MAXIMA (Millimeter Anisotropy eXperiment IMaging Array). They detected patterns in the cosmic microwave background (CMB), supporting the idea of inflation in the early universe and proving that the universe is flat, not curved. The results, announced in 2000, confirmed the findings of a competing experiment, BOOMERanG (Balloon Observations Of Millimetric Extragalactic Radiation and Geophysics), co-led by one of Richards’ former students, the late Andrew Lange, which were announced a month earlier. Together, MAXIMA and BOOMERanG provided convincing evidence that the reigning theories of cosmic birth and evolution were correct.

“A subset of cosmological theories, those involving inflation, dark matter and a cosmological constant, fit our data extremely well,” Richards said at the time. “This is a good confirmation of the standard cosmology, and a large triumph for science, because we are talking about predictions made well before the experiment, about something as hard to know as the very early universe.”

MAXIMA used highly sensitive helium-cooled detectors, called bolometers, to measure minuscule fluctuations in the background radiation left over from the Big Bang.

Richards also pioneered detectors based on superconducting sensors and instrumented with superconducting quantum interference devices (SQUIDs), which were used on an experiment called POLARBEAR in the early 2010s to measure the polarization of the CMB. Variations on these detectors are still used today for even more detailed measurements of the CMB, such as those by the South Pole Telescope.

“He needed very sensitive detectors, and of increasingly high frequency, and I eagerly took that on and helped him with these devices,” said John Clarke, one of the pioneers of SQUIDS as detectors and a UC Berkeley professor emeritus of physics. “People in my group built the devices for him. I was always very interested in making the SQUIDS go to ever higher frequencies, and the reason I did that was largely driven by what Paul needed. Our long-running collaboration ultimately resulted in 22 joint publications.”

“That was really a theme in Paul’s career, that he would develop the really difficult, innovative technologies and then go out and measure something very important with them,” said Adrian Lee, a UC Berkeley professor of physics and Richards’ former postdoctoral fellow who later became his collaborator and now leads a group exploring the polarization of the CMB radiation. “Bringing that blockbuster technology forward was a big part of his career.”

A makerspace in the UC Berkeley physics department is being dedicated to Richards in recognition of his belief that building equipment is an important part of learning. Funded in part by a donation from Richards’ family, the Paul L. Richards Innovation Lab will provide valuable hands-on experience with equipment and projects that students are likely to encounter in their scientific career.

From solid-state physics to astrophysics

Richards was first introduced to infrared spectroscopy as a UC Berkeley graduate student in the late 1950s and eventually began building state-of-the-art detectors for far infrared wavelengths — a relatively unexplored region of the spectrum — to study new materials. With detectors he built as a member of the UC Berkeley physics faculty a decade later, he was able to detect a central feature of superconductors — the energy gap — that determines the temperature at which a material becomes superconducting.

In the 1970s, one of his physics colleagues, Charles Townes — the Nobel Prize-winning inventor of the laser who had moved into the field of astrophysics — suggested that these detectors might be used to measure the frequency spectrum of radiation left over from the Big Bang. Though measured in the microwave range in 1965, the radiation had not been measured in the infrared, primarily because infrared detectors at the time were primitive and measuring such radiation was difficult because most of it is blocked by Earth’s atmosphere.

Richards took Townes up on his proposal and built and flew the first helium-cooled infrared spectrometer on balloons, to get above the atmosphere, in the mid-’70s. That and later balloon experiments helped prove the blackbody nature of the CMB, that is, its emission spectrum matched that of an object in thermal equilibrium.

MAXIMA and Boomerang subsequently explored the spatial fluctuations at different scales and by 2000 had data from which other features of the universe could be deduced, including its curvature, its age and the proportions of normal matter (5%), dark matter (27%) and dark energy (68%).

“People like to say that the cosmic microwave background is the Rosetta Stone of cosmology,” Lee said. “That’s a bit hyperbolic, but it’s actually true. We really are learning all these things about the universe from the cosmic microwave background.”

Lee eventually took over leadership of the research group and initiated the POLARBEAR experiment, with Richards as a collaborator. Lee currently leads a successor experiment, the Simons Array, based at the James Ax Observatory at 17,000 feet altitude in Chile.

Paul Linford Richards was born June 4, 1934, in Ithaca, New York, and eventually moved with his family to Riverside, California, where he attended Riverside Polytechnic High School. He enrolled at Harvard University in 1952, where he graduated summa cum laude with a degree in solid state physics in 1956. He earned his Ph.D. in physics from UC Berkeley in 1960, then took a postdoctoral year at Cambridge University in the United Kingdom.

Richards subsequently worked for six years at Bell Telephone Laboratories in Murray Hill, New Jersey, conducting work in solid-state physics. He returned to UC Berkeley in 1966 as a member of the physics faculty. He retired as a professor emeritus in 2005.

Marvin Cohen, UC Berkeley professor emeritus of physics, met Richards when Cohen was a postdoctoral researcher at Bell Laboratories. He had known about Richards’ graduate work at UC Berkeley on superconductivity and quizzed him about it when they met.

“I still remember how impressed I was by his high standards and the way he was able to make me, a theorist, understand the details of his experiment,” Cohen said.

After Cohen joined the UC Berkeley physics faculty in 1964, he worked hard to recruit Richards to the department. Richards accepted the faculty position, but to Cohen’s dismay, changed fields to pursue research in astrophysics and cosmology.

“It was astonishing to watch Paul quickly move from the cutting edge of one research area to that of another,” Cohen said. “His accomplishments and those of his group of exceptional students and postdocs had an enormous impact, especially in the field of cosmology.”

Clarke first met Richards at Cambridge University in 1967, when Clarke was finishing his graduate studies and Richards was a new assistant professor at UC Berkeley. Clarke was impressed with Richards, both personally and for his scientific knowledge, and asked to come to UC Berkeley to be Richards’ postdoctoral fellow. Unfortunately, Richards didn’t have funding for a second postdoc, but a new faculty member, Gene Rochlin, was looking for one and was glad to take Clarke on.

“From a practical point of view, Paul was unquestionably my mentor,” Clarke said. “I came to Berkeley because of Paul Richards. He taught me an enormous amount about experimental physics and became a close friend and long-term collaborator. His impact on my life and my scientific career were enormous.”

Richards was a member of the National Academy of Sciences and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences. He received the Button Prize of the Institute of Physics (U.K.) for Outstanding Contributions to the Science of the Electromagnetic Spectrum in 1997, the Frank Isakson Prize of the American Physical Society for Optical Effects in Solids in 2000, the Dan David Prize for Cosmology in 2009, the 2011 Medal of the Schola Physica Romana and the Tomassoni Prize of the University of Rome for Cosmology, and the Cocconi Prize of the European Physical Society for Particle Astrophysics in 2011. He also was named California Scientist of the Year in 1981. He received fellowships from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation, the J.S. Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, and — three times — from the Adolph C. and Mary Sprague Miller Institute for Basic Research in Science.

Richards has published more than 300 papers on infrared and millimeter wave physics, including the development of measurement techniques, especially new detectors, and the application of these techniques to many physical problems. He is survived by Audrey Jarratt Richards, his wife of 59 years; their two daughters, Elizabeth Brashers of Oakland and MaryAnn Pearson of Berkeley; a sister, Mary Luch of Baltimore, Maryland; and two grandchildren.

2024

Jack Welch

William John (Jack) Welch (1934-2024)

Jack Welch pioneered the field of millimeter-wavelength astronomy, discovered the first polyatomic molecules in space, and was a strong advocate of SETI

by Imke de Pater, Jean Turner, Eric Welch and Carl Heiles

William John (Jack) Welch, emeritus Professor in both the Departments of Astronomy and of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science (EECS) as well as former Director of the Radio Astronomy Laboratory at the University of California at Berkeley, died on March 10, 2024, at the age of 90.

Jack was a highly skilled experimental radio astronomer who played an important role in the discovery of polyatomic chemistry in interstellar gas and in the development of millimeter and submillimeter interferometry, which paved the way for the Atacama Large Millimeter/Submillimeter Array (ALMA). He was also the principal designer of the Allen Telescope Array at the Hat Creek Observatory, which serves as

a model for large, lower frequency observatories such as the Square Kilometer Array.

Jack’s contributions to radio science were recognized nationally and internationally, including his election to the National Academy of Sciences in 1999, the Jansky Lecturer Award in 2001, and the URSI Balthasar van der Pol Gold Medal in 2008. Jack also held the Marilyn and Watson Alberts Chair for the Search for Extra Terrestrial Intelligence (SETI) at UCB between 1998 and 2011.

Jack was born on January 17, 1934, in West Chester, Pennsylvania. His ancestors had developed the Welch Food Company, which pressed, bottled and sold Welch’s Grape Juice. Jack’s great-grandfather, Thomas Bramwell Welch (1825 [England] –1903 [Philadelphia]) invented the Juice by applying the work of Pasteur to keep it fresh. Jack’s grandfather, Charles Edgar Welch (1852 – 1926) made Welch’s a commercial success. Charles had five sons, the youngest was Jack’s father, William Taylor Welch (1890 – 1961), ran a manufacturing business called Ajax Flexible Coupling.

William (Jack) Welch moved away from the business activities of his father and grandfather by pursuing an academic career. He was an undergraduate at Oberlin and transferred to Stanford University to obtain a BA in Physics in 1955. He accomplished his Engineering Science Ph.D. in 1960 at the University of California, Berkeley, studying Antennas. As a newly minted engineering Ph.D., he received three unsolicited job offers: Bell Labs, Dartmouth and Berkeley; perhaps a Ph.D. in Engineering Science was ideal for the post-Sputnik era. Thanks to his liking of the Californian weather and his passion for tennis, Jack chose Berkeley, and joined the faculty of UCB’s Electrical Engineering Department (which now includes Computer Science – the EECS Department) in 1960. With his keen interest in electromagnetics, he soon formed a natural symbiotic coupling to Berkeley’s Radio Astronomy Laboratory (RAL), which just two years earlier had been founded by Professor Harold Weaver in the Department of Astronomy as one of the first Organized Research Units.

In 1971 Jack became a 25% faculty member in the Astronomy Department, and at about the same time started serving a 25-yr long term as the Director of RAL. In 2005, when RAL’s millimeter antennas were moved to Cedar Flat (CA) and combined with Caltech’s antennas to form the Combined Array for Research in Millimeter-wave Astronomy (CARMA), Jack retired from both departments.

In the late 1960’s Jack and physics Professor Charles Townes, together with their graduate students, made the first detections of ammonia and water in the interstellar medium (ISM) using RAL’s newly commissioned 20-ft radio telescope at UCB’s Hat Creek Radio Observatory. They also used this telescope to detect ammonia gas closer to home, in the planets Jupiter and Saturn. Over the next decades, this seminal discovery of the first polyatomic molecules in space triggered the detections of dozens of additional interstellar molecules by astronomers, enabled detailed studies of star formation in interstellar clouds, and launched the field of astrochemistry. Before these detections, the conventional wisdom had been that nothing larger than a diatomic molecule could be formed in interstellar clouds. We now know that nothing could be further from the truth. We can have plentiful molecules as complex as alcohols, sugars, and amino acids in molecular clouds. For complex molecules to be so plentiful, not only must they form efficiently via extensive chemical networks and solid-state surface reactions on interstellar dust grains, but also must be shielded from destruction and dis-association due to stellar ultraviolet radiation by those same grains. The implied gas densities were much higher than those expected or implied by previous observations of the ISM, even high enough to form new stars.

When Jack saw the connection between dense molecular gas and star formation, he realized the importance of mapping the structure and kinematics of the dense molecular gas – and that this could only be accomplished by mapping emissions from rotational lines in cold molecular clouds. Such lines are present only at millimeter wavelengths. Accordingly, moving to higher radio frequencies was key to mapping the dense molecular gas. Consequently, Jack led the development of the Hat Creek Interferometer to become the first millimeter-wave interferometer.

Observations with this instrument provided the first maps of molecular line emission at arcsecond resolution in massive star forming regions, including important studies of molecular line and maser emission in Orion, W49, K3-50, and W3(OH). Jack was the first to recognize that there were “too many compact HII regions” in the giant star-forming region W49 to be consistent with their dynamical ages, and that some mechanism must inhibit their expansion. In addition, Jack’s insisted that there was a stellar object at the position of the water masers in W3(OH) in spite of a lack of infrared continuum emission, even at wavelengths as long as 30 microns. Jack and his student discovered a hot molecular core in HCN emission at this location. The extremely high extinction toward this young protostellar object ruled out most infrared observations and foretold the need for interferometry at submillimeter wavelengths.

Jack left a lasting legacy as the pioneer in the field of millimeter wavelength interferometry, first by building the Hat Creek Interferometer, then expanding it into the Berkeley-Illinois-Maryland Array (BIMA). The success of these instruments led to the construction of even more capable telescope arrays – CARMA, and ultimately the Atacama Large (sub)Millimeter Array (ALMA). Jack served as chair of the advisory committee for the Smithonian’s Submillimeter Array (SMA) for a remarkable 13 years (1989-2002), providing invaluable guidance through the construction of this interferometer. With the SMA, as with many of his other projects, Jack was always upbeat with positive suggestions and encouragement, no matter how grim the situation appeared. This is the Jack that many of his former students and colleagues remember.

Maryland Array. Credit: Jill Tarter.

Jack’s realization of the biological importance of his detection of the first two molecules in space was related to the Miller-Urey experiment (amongst others) that showed the synthesis of amino acids when sparked by electric pulses. As the first to hold UCB’s chair for the search for extraterrestrial intelligence (the Marilyn and Watson Alberts Chair), he emphasized the importance of seeking intelligent life beyond Earth and advocated that SETI was a legitimate science. He was one of the founding members of the SETI Institute’s Board of Directors. After Jack’s retirement in 2005, he moved on and played a central role in the design and development of the Allen Telescope Array (ATA), the first observatory built specifically to conduct SETI research.

Jack’s enthusiasm, kindness, and guidance inspired many students who went on to make their own contributions to radio astronomy. Jack was always friendly and approachable, exceptionally kind, and trusting; He really had a knack to bring out the best in people. In addition to teaching courses in EECS and Astronomy, he sometimes taught a full radio astronomy course to just a single graduate student, if the student showed an interest in the field. He also was generous with his time, and on occasion loaned, for several years, his (expensive) equipment to graduate students in other departments. RAL, under Jack’s leadership, was a thriving place, with incredibly talented staff and students. The atmosphere was pleasant, conducive to perform one’s best work, whether it was building equipment and/or using the telescopes for science. A total of 27 students obtained their degree under Jack’s guidance. Numerous social events were organized at Jack and (his wife) Jill’s house, a tradition that had been started by the former Director (and Founder) of the Radio Astronomy Lab, the late Professor Harold Weaver.

In addition to being passionate about building the most capable telescopes, he loved flying. In the early 60s he co-founded a group called the “Astronomical Flying Society”. A major reason for the club was to fly to and from Hat Creek, instead of driving back and forth. Jack was an expert pilot with a masterful ability to confront emergency situations: he once made a forced landing after the engine seized and the windows fogged up in the mountainous terrain of western Colorado when he glided the plane down to land on a jeep road. An impressive accomplishment, remembered by many people – especially those who were passengers in the plane! He ultimately sold his Cessna to help fund construction of the ATA.

Jack is survived by his wife, Jill Tarter; his former wife, Juliet Wilson Welch; his son Eric, daughters Jeanette and Leslie, and step daughter, Shana Tarter. Jack died peacefully at home, with Jill at his side. Just two hours earlier, his son was visiting, and his two daughters were on Zoom from their homes across the country.

Jack leaves a legacy that transcends his contributions to radio astronomy, astrochemistry, and the search for extraterrestrial intelligence. His pioneering spirit, dedication to scientific exploration, and impact on the field will be remembered and celebrated by colleagues, students, and the broader scientific community. He will be greatly missed.

2023

Erik L. Kollberg

Erik L. Kollberg: 1937-2023. Erik passed away on October 14, 2023.

Erik Kollberg was an outstanding engineer, scientist, and internationally recognized expert in millimeter-wave and sub millimeter-wave radio technology. He was a pioneer in the development of high frequency (THz) radio astronomy instrumentation, including devices, components, systems, and telescopes. He was a friend and colleague to hundreds of scientists and engineers around the globe and his passing will be strongly felt by the many individuals he worked with and befriended over the years. Most of his career was spent at Chalmers University in Sweden where he worked as a beloved teacher and distinguished professor for more than 50 years. A very detailed and complete biographical compendium of Professor Kollberg’s work and pioneering contributions to the THz community can be found in: P. H. Siegel, “Terahertz Pioneer: Erik L. Kollberg “Instrument Maker to the Stars”,” in IEEE Transactions on Terahertz Science and Technology, vol. 4, no. 5, pp. 538-544, Sept. 2014, doi: 10.1109/TTHZ.2014.2344191. https://doi.org/10.1109/TTHZ.2014.2344191

2022

Daniel Grischkowsky

Daniel Grischkowsky: Terahertz Pioneer, Mentor, and Friend

Although the technological and societal benefits of terahertz science have been known for a long time, it took a few pioneers in the 1970’s, 1980’s and 1990s to lead the way in scientific discovery, where the path and outcomes were far from certain. Dan Grischkowsky was one such pioneer.

Grischkowsky’s formative years began in 1969 as a scientist at the IBM Watson Research Center. After a very productive career at IBM, he joined the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering (ECE) at Oklahoma State University (OSU) in 1993. During his career of 46 years, he wrote 179 papers in prestigious, international peer-reviewed journals and had more than 11,400 citations. For the IRMMW-THz community, he is most well known as the inventor of terahertz time-domain spectroscopy, a technique that is now used in hundreds of research labs worldwide, as well as a growing number of industrial and commercial settings. He was a Fellow of the American Physical Society (1982), Fellow of the Optical Society of America (1988), and a Fellow of the IEEE (1992). He received the Boris Pregel award from the New York Academy of Sciences (1985), the Kenneth J Button Prize from the International Society of Infrared, Millimeter and Terahertz Waves (2011), and both the R. W. Wood award (1989) and the William F. Meggers award (2003) from the Optical Society of America.

These accolades are impressive, but he made a much deeper and lasting impression on those fortunate few whom he mentored. In the mind of his budding graduate students, his admonitions to be “smart and lazy” seemed at times to contrast with his frustrating expectation of crystal clear, unassailable results. As you presented your work, his drawn out, skeptical “Well…” rang clearly over the lab floor casting doubt on your qualifications in the minds of all those present. You quickly learned to be your own greatest critic. But in time you also learned that his approach wasn’t malevolent or condescending, it was just good training. His mentorship mirrored his research style, an unwavering “search for truth and beauty,” an example which lives on even today in his collected works. In retrospect, I can think of no lesson of greater importance. Over time, Dan became more than a mentor, but also a colleague and friend, as he was to so many students, postdocs, and fellow scientists. Though terahertz will never be the same without Dr. G, his legacy will continue, as a pioneer, mentor, and friend.

Dan retired from OSU in June 2016 and was the ECE Emeritus Regents Professor until his passing in June of 2022. He is survived by his three children Daniela, Timothy, and Stephanie, and their mother Frieda.

Contributed by John O’Hara, Oklahoma State University, June 28, 2022

To read a detailed technical biography of Professor Grischkowsky please invoke the two article links below (into and main text):

intro, Peter H. Siegel, “THz Pioneers: Daniel R. Grischkowsky: We Search for Truth and Beauty,” IEEE Trans. on Terahertz Science and Technology, vol. 2, no.4, pp.377-382, July 2012.

Thomas G. Phillips

Thomas G. Phillips, the John D. MacArthur Professor of Physics, Emeritus, passed away on August 6, 2022. He was 85.

Phillips was a pioneer in observational astronomy, opening a new window to the cosmos in the millimeter and submillimeter wavebands of light. He led national and international teams that developed both ground- and space-based telescopes to observe in this portion of the electromagnetic spectrum, which allows astronomers to peer into regions of space enshrouded by large amounts of dust and gas. Phillips made several discoveries using millimeter and submillimeter instruments, including the detection of the signatures of atoms and molecules that form the ingredients of new stars and planetary systems.

Phillips came to Caltech as a visiting associate in radio astronomy in 1978, and he joined the faculty as a professor of physics in 1979. He was named Altair Professor of Physics in 2004 and John D. MacArthur Professor of Physics in 2011. He retired in 2013.

In the 1980’s, Phillips led the development of Caltech’s Owens Valley Radio Observatory (OVRO) millimeter-wave interferometer as well as the Caltech Submillimeter Observatory (CSO) in Hawai’i (which is currently being decommissioned and moved to Chile).

As the director of the CSO from 1986 to 2013, he traveled back and forth to the telescope’s site atop Maunakea, where he would observe the cosmos at night, and, according to professor of physics Sunil Golwala, would play golf in the morning.

“He loved to golf,” says Golwala, who has served as the director of CSO since 2013. “I was a postdoc when I arrived at Caltech, and CSO was in full swing under Tom’s leadership. He ran the observatory like a physics experiment. We were welcome to test instruments there, and he encouraged us to figure things out from scratch.”

In the late 1970’s, while working at Bell Laboratories in New Jersey, Phillips pioneered the design and optimization of a new type of detector for submillimeter astronomy, called the SIS receiver (for superconductor-insulator-superconductor). Other scientists came up with a similar device at the same time, but, says Phillips’s longtime colleague and friend Jonas Zmuidzinas (BS ’81), the Merle Kingsley Professor of Physics and director of Caltech Optical Observatories, “it was Tom who took the device and showed how it could be used in astronomy.”

The SIS devices would reshape astronomy. They made their debut at OVRO, followed by CSO in Hawai’i, and later the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA) in Chile, the world’s most expensive ground-based observatory in operation today. SIS receivers on ALMA enabled the recent black hole images produced by the Event Horizon Telescope collaboration, images of young planets still under construction in the disks around young stars, and much more. They were also used on the European-led Herschel Space Observatory, which detected far-infrared and submillimeter light from 2009 to 2013.

“The role that Phillips and his colleagues at Bell, and later Caltech, played (as well as Paul Richards and his colleagues at UC Berkeley) in bringing these devices to the attention of the THz community, can never be overshadowed,” wrote Peter Siegel, Phillips’s collaborator on Herschel, editor-in-chief of the IEEE Journal of Microwaves, and a retired senior research scientist at JPL, which Caltech manages for NASA, in an essay called “Terahertz Pioneer: Thomas G. Phillips.” (THz or terahertz is another term for submillimeter light and refers to frequencies rather than wavelengths.)

A symposium held in Phillips’ honor in 2009 celebrated his crucial contributions to the development of submillimeter astronomy on the ground and in space. “This is the legacy of Tom Phillips, who for nearly four decades has been at the center of the most important developments in this field,” stated the conference introduction.

Phillips’s role in the Herschel Space Observatory began long before the mission launched in 2009. In fact, the seeds for the HIFI instrument on Herschel (Heterodyne Instrument for the Far-Infrared) began with Phillips as far back as the late 1970’s, when he had been pushing for a large submillimeter and infrared space observatory called the Large Deployable Reflector. NASA funded Phillips and colleagues to explore the concept, and he and his colleagues at both Caltech and JPL worked on the SIS devices (in fact, Phillips helped start the Microdevices Laboratory at JPL).

Ultimately, NASA would choose to not build its own space mission and instead joined forces with the European Space Agency to participate in Herschel. Phillips served as the U.S. principal investigator for the mission’s HIFI instrument, which contained his SIS receivers.

“Tom Phillips played a huge role in ensuring the success of the Herschel Space Observatory and of HIFI, in particular,” says Paul Goldsmith, NASA Herschel project scientist. “His eminence and expertise helped get NASA to join the project, and his relentless enthusiasm for spectroscopy led to many important decisions about HIFI and related software that made it a very popular tool for studying the astrochemistry of interstellar space and how stars are formed and interact with their surroundings.”

Phillips was born on April 18, 1937. His father “had studied mechanical engineering before being forced to give up his formal education to assist his widowed mother at her Public House,” according to Peter Siegel’s essay on Phillips.

He received bachelor’s (1961), master’s (1964), and doctorate (1964) degrees from the University of Oxford in England, studying low-temperature physics. During this time, he was appointed to a Junior Research Fellowship at Jesus College. In 1968, after one year as a research associate at Stanford University and two years as a lecturer at Oxford, Phillips moved to Bell Labs, where he developed his first detector for submillimeter astronomy (called an InSb hot-electron bolometer) and used it to study atoms and molecules making up the interstellar medium, or the space between stars.

Working at various telescopes, including Kitt Peak National Observatory, Caltech’s 200-inch Hale Telescope at Palomar Observatory near San Diego, and the Kuiper Airborne Observatory, Phillips detected numerous new atomic and molecular species in the interstellar medium, including the surprisingly abundant neutral carbon atom. This latter result has greatly enhanced our understanding of how molecular clouds, the birthplace of stars, form and evolve.

Part of the impetus for these studies, recalls Zmuidzinas, came from Phillips’s colleagues, who worked down the hall from him at Bell Labs: Keith Jefferts, and Arno Penzias and Robert Wilson (PhD ’62), who shared the Nobel Prize in Physics in 1978 for the discovery of the cosmic microwave background radiation.

According to Siegel’s essay, “Phillips brazenly walked up to Penzias and told him that his diode mixer had very poor sensitivity, and that he should be able to do much better with an InSb device. … Penzias reacted in a very positive way to the criticism of this rather brash young physicist—he challenged Phillips to go and make a better receiver!”

Phillips did go and make a better receiver using the InSb device, and later would co-invent an even better device, the SIS receiver. Zmuidzinas remembers when he first saw spectral data from Phillips’s SIS device—it showed numerous “fingerprints” of molecules in the Orion Nebula.

“It was stunning to see the spectrum, a huge forest of information,” Zmuidzinas says. “This work ended up being one of Tom’s most cited papers.” The Orion survey formed the centerpiece of the doctoral thesis of Geoff Blake (PhD ’86), now a professor of cosmochemistry and planetary science and professor of chemistry at Caltech.

“It’s like a forensic scientist dusting a surface of a desk to look for fingerprints,” Golwala says. “Tom’s SIS mixer is like this—it lets you see the fingerprints of molecules in space that are otherwise invisible.”

Blake notes that he took two key lessons from Phillips’s mentorship: Think deeply about what is possible and what physics permits, and have a long-term plan to enable discovery. “Tom insisted, once the survey was done, that a single figure of all the data be generated. I am sure he had an idea of it in his head, that he had thought about the intricate physics,” Blake says. “In those days, it took minutes for the data to be loaded before it could viewed and studied. I still vividly remember that moment when it was revealed, late one night. Tom knew communication was just as important as the discovery itself, and his life and work have opened up new vistas for exploration.”

“Tom had an incredible appetite for work, and kept accreting projects,” says Zmuidzinas. “But even with so much on his plate, he was always very calm and methodical. He could expertly navigate complex and difficult situations.”

Zmuidzinas, who did his undergraduate work at Caltech and then later returned to the Institute, at Phillips’s urging, to take a faculty position, recalls that Phillips would gather his group every day for lunch. “We would walk to Grant Park at the corner of Michigan and Del Mar, stopping at Eddie’s Market (now the Ginger Corner Market) for sandwiches. We would sit on the grass in a big circle and talk about what was happening, research or otherwise. He treated his group like a big family—that was Tom in a nutshell.”

Phillips, who held an honorary doctorate from l’Observatoire de Paris, was a fellow of the American Physical Society and a member of the American Astronomical Society (AAS), the International Astronomical Union, and the International Union of Radio Science. From 1997–2002, he was the AAS representative to the U.S. National Committee for Radio Science.

In 2010, Phillips was awarded the NASA Exceptional Public Service medal for his work on HIFI. In 2008, he was chosen to be honored at the Templeton Xiangshan Conference in Beijing, China, at a celebration of the 400th anniversary of the invention of the telescope. The AAS awarded him the Joseph Weber Award for Astronomical Instrumentation in 2004.

Phillips is survived by his wife Jocelyn Keene, who is an astrophysicist and was a postdoc, senior research fellow, and member of the professional staff at Caltech and JPL for a total of 24 years. Phillips is also survived by their daughter Elizabeth, and his children Claire and Stephen.

WRITTEN BY Whitney Clavin, AUGUST 2022. Reproduced with permission from California Institute of Technology (https://www.caltech.edu/about/news/caltech-mourns-the-passing-of-thomas-g-phillips)

For a detailed TECHNICAL BIOGRAPHY on Tom Phillips career see:

https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=6287045

Toshitaka Idehara

It is with great sadness and heavy heart that we inform you of the passing of Prof. Toshitaka Idehara on March 18, 2022, at the age of 81. He is the founder and the first director of Research Center for Development of Far-Infrared Region, University of Fukui (FIR UF) and professor emeritus of University of Fukui.

Prof. Toshitaka Idehara graduated from Kyoto University in 1963 and received his Master and Doctoral degrees in Science in 1965 and 1968, respectively, also from the same university. He started his career as a lecturer in the Faculty of Engineering, Fukui University (now University of Fukui) from 1968. In the early time of his research (1963-1980), he studied negative absorption phenomena in plasma and the instability in electron beam-plasma system. From around 1980, he started researches on development of high-power millimeter and terahertz wave sources based on vacuum electronics and their applications to material sciences and various scientific researches. He is a pioneer in the development of high-frequency gyrotron. After the foundation of FIR UF in 1999, a series of various types of sub-THz gyrotron (FU series and FU CW series) were developed and were used for various scientific researches. One milestone was the achieved second-harmonic oscillations at more than 1 THz in 2005. Examples of the research subjects using his developed gyrotrons are electron spin resonance (ESR) spectroscopy, dynamic nuclear polarization-nuclear magnetic resonance (DNP-NMR) spectroscopy, X-ray detected magnetic resonance (XDMR) spectroscopy, direct measurement of hyperfine splitting of positronium, light emission from semiconductors and cancer therapy.

He served as the Editor-in-Chief of International Journal of Infrared and Millimeter Waves (Journal of Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz Waves) from 2004 to 2010. From 2011, he is the Editor-in-Chief Emeritus together with Kenneth J. Button. He was an active member of board of directors (2010-2018) and Councilor (2019-2021) of Terahertz Technology Forum, Japan. He was also a member of the 182nd Committee on Terahertz Science, Technology and Industrial Development, Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (2008 -2018). He has hosted IRMMW-THz 2018 conference in Nagoya as the Co-Chair. He won Science and Technology Award from Minister of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology (MEXT) of Japan in 2009 for the work “Study on High Power THz Radiation Sources –High Harmonic Gyrotrons.” He received Fukui Prefectural Academic Grand Prize of Science from the Governor of Fukui Prefecture for the work “Development of High Power Terahertz Radiation Sources –Gyrotrons and their Applications to Terahertz Technologies.” in 2010. He was also awarded Kenneth J. Button Prize with the outstanding contribution to science of infrared, millimeter and terahertz waves, in the 41st International Conference on Infrared, Millimeter and Terahertz Waves, Copenhagen, September 25-30, 2016. Recently, in 2020, he was awarded the Order of the Sacred Treasure, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon, from the Japanese Government.

He was a great scientist and at the same time a wonderful person, with a bright, upright and kind personality. Many students and researchers trust him and gather around him. Therefore, he had many friends not only in Japan but all over the world. Even now, researchers from around the world visit, stay and carry out active researches at FIR UF, which he founded.

Prof. Idehara, a beloved and cherished mentor, colleague and friend, will be greatly missed by many, but never will be forgotten.

Prof. Masahiko Tani

Prof. Yoshinori Tatematsu

Prof. Seitaro Mitsudo

Research Center for Development of Far-Infrared

University of Fukui

Fukui, 910-8507, Japan

March 28, 2022

2020

Charles Schmuttenmaer

In 2020 we received the sad news of the passing of our friend and colleague, Professor Charles Schmuttenmaer of Yale University, New Haven, CT, USA, on Monday, July 26, 2020.

Charles (Charlie) Schmuttenmaer was born on August 5, 1963, in Oak Park, IL. He received his bachelor’s degree in Chemistry in 1985 from the University of Illinois, Urbana–Champaign where he began work in the far infrared (FIR) spectroscopy of gas phase rotational lines with H. S. Gutowsky. His graduate work in the R. J. Saykally group at University of California, Berkeley, included development of a side-band generation source for continuous scanning high resolution gas phase FIR spectroscopy. After his PhD in 1991, Charlie did postdoctoral work with R. J. D. Miller at the University of Rochester working on ultrafast solid state photoemission. He joined the Yale Chemistry faculty in 1994 and immediately employed his expertise in FIR and ultrafast spectroscopy to build a world-renowned program in terahertz time domain spectroscopy (THz TDS).

He initially focused on studies of polar solvents, binary mixtures and nano-confined water. He developed the variable path length solution cell, which has proven indispensable to achieve high precision complex dielectric response measurements for strongly absorbing solvents. In pursuit of measuring solvent reorganization about a solute after electron transfer, Charlie began working on time resolved terahertz spectroscopy (TRTS). This work led to his developing a method to deconvolve the overlap between the pump pulse and THz probe pulse to attain the earliest photo-induced response. Using this analysis, he reported the first ps time-resolved frequency-dependent complex conductivity measurements using TRTS. Upon subjecting this data to a number of modelling approaches, he found that the newly proposed Drude–Smith model was the most successful, and it has since become the standard for interpretation of THz transient photoconductivity.

Charlie’s command of both measurement and theory enabled him to show through a series of molecular crystal measurements that the character of the atomic displacements associated with the THz absorption lines progressed from strongly intermolecular to intramolecular. He established THz polarimetry techniques and analysis using cleverly designed chiral metamaterials. Charlie’s most recent scientific passion was to apply TRTS to photovoltaic materials and was a founding member of the Yale Green Energy Consortium.

It is not possible to list all of Charlie’s scientific achievements. These are reflected in his various awards and fellowships in the Royal Society, the APS and the AAAS. Beyond this, Charlie was instrumental in creating a vibrant and collegial community. From organizing innumerable international symposia and conferences, to his exuberant talks and discussions, Charlie exuded a joy for scientific exploration and life. We send our heart-felt condolences to his family.

Andrea Markelz, December 31, 2020

Moti Lal Rustgi Professor of Physics

University at Buffalo

Buffalo, NY 14260 USA

Derek Martin

Professor Derek Martin died on 14 February 2020 aged 91. Derek was a pioneer of the study and use of the Terahertz electromagnetic spectrum. His most famous instrument, the Martin-Puplett polarising interferometer, was used by him and others in a variety of applications from measurement of the cosmic microwave background to diagnosis of plasma in nuclear fusion machines.

Derek was honorary secretary of the Institute of Physics for 10 years (1984 – 1994). He was instrumental in choosing the new chief executive and helped him to implement new strategies and transform the IOP into the influential and vigorous society, with greatly enlarged membership, that it became. He was an IOP representative at meetings of overseas national and international societies and a leader of the UK delegation to the International Union of Pure and Applied Physics. He was also editor of the journal Advances in Physics.

After obtaining a PhD from Nottingham in 1954 he came to Queen Mary College (now Queen Mary University of London) as an assistant lecturer in physics. He was promoted successively to lecturer, reader, and professor. For several years he served as head of department and later as dean of faculty. He was also a University of London senator. He was made an honorary fellow of Queen Mary in 1996.

He arrived at Queen Mary committed to a search for a better understanding of the exotic phenomena of superconductivity and of strong magnetism in solids. He decided to seek ways to generate and detect electromagnetic waves in an unexplored part of the spectrum, that between the infrared and microwaves, wavelengths around 1 mm, because he believed that such waves would probe the large-scale collective motions of atoms.

Before that could be done there were substantial technical impediments for him to overcome. One of his first steps was to build a miniature refrigerator to reach temperatures within a degree or two of absolute zero and to operate a superconducting detector at this ultra-low temperature in order to be able to detect signals of extremely low strength.

His belief was soon proved to be right and he embarked on the central-path of his scientific work: the development of ever-more subtle techniques for detecting and analysing submillimetre waves and applying them in studies of the structures of matter. This took him, and colleagues at Queen Mary, beyond solid state physics, into astronomy and cosmology, into the remote-sensing of ozone-related stratospheric chemistry from aircraft, high-altitude balloons and satellites, and into diagnostic studies of energy-generating plasma machines. His work rapidly gained wide recognition and many visitors came to Queen Mary to work with him and to learn the elegant and sensitive measurement techniques he had developed, then to return to pursue such work in their own laboratories in the USA, Japan, Australia, Canada, Italy, Germany and China.

He initiated several of the research areas in the physics department: polymer physics which grew into molecular electronics and condensed matter physics and the inventions of instruments which were developed by a company which became QMC Instruments, initially based at Queen Mary, but now at Cardiff. He also collaborated with colleagues in electrical engineering.

As a member and chairman of the Astronomy Committee of the Science Research Council through the 70s, he was one of the first to understand the importance of molecules in space and their detectability in the submillimetre wavelengths. He was centrally involved in proposing what eventually became the James Clerk Maxwell Telescope, the world’s largest and most successful submillimetre facility. This gave the UK a world-lead in the field which continues to this day.

He also initiated the participation of the UK in the first satellite-borne infrared telescope, IRAS, which revealed the rich infrared sky which had hitherto been obscured by the Earth’s atmosphere. Derek Martin invented the polarising Michelson interferometer, the Martin-Puplett design that was used successfully to make early observations of the cosmic microwave background from balloon and ground-based platforms.

Another measure of his huge legacy is that many of his colleagues at Queen Mary have been leading figures in the use of these ground-based and satellite-borne infrared and submillimetre telescopes. In addition, many of his students have gone on to occupy prestigious positions in astronomy and high-tech organisations in the UK and abroad.

Derek’s interest in instrumentation, and particularly for the experimentally difficult part of the electromagnetic spectrum where optical and radio techniques approach each other, led to millimetre-wave diplexers, power meters and other devices. These were later developed further by his students and associates who have commented that it had been a real pleasure to work with Derek, that he was always helpful and considerate, as well as being an outstanding scientist.

In recognition of the seminal importance of his work in measurement science, Derek was awarded a number of scientific prizes including the Kelvin Award of the Institute of Electrical Engineering, the Metrology Prize of the National Physical Laboratory and the Kenneth J Button Prize for pioneering terahertz polarization interferometry.

Derek spent 1966 as visiting professor at the University of California at Berkeley at the time of student unrest there. This perhaps stood him in good stead because, soon after his return, he was elected dean of the faculty of science in the college, just as the student revolts spread from the USA to universities in Europe. Queen Mary was less disrupted than many of the other leading universities here. One possible factor in this was the decision to replace the then-conventional rigid science-degree programmes with a modular science-degree geared to the developing interests of individual students. As dean for science, Derek had to find a pattern of implementation persuasive to senior and strong-minded academic colleagues across the faculty. That pattern has since spread to other faculties in the college and to many other universities.

However, notwithstanding these many and diverse activities, he remained primarily a teacher and researcher in his subject. His work has contributed substantially to the Queen Mary’s success and high international reputation.

Peter Kalmus

Queen Mary University of London

For a detailed professional biography on P{professor Martin please see:

intro, Peter H. Siegel, “THz Pioneers: Derek H. Marin: The Mesh that Helped Ensnare the Cosmic Microwave Background,” IEEE Trans. on Terahertz Science and Technology, vol. 5, no. 3, pp. 325-331, May 2015.

Maurice F. Kimmitt

We have just received the sad news of the passing of our friend and colleague, Professor Maurice Kimmitt, of the University of Essex.

Maurice was active for many decades in the field of infrared, millimetre and terahertz waves and his book “Far-infrared techniques”, published by Pion Ltd. in 1970, was one of the first in the field. During his long career, which began at RRE Malvern (the Royal Radar Establishment) and continued at the University of Essex, Maurice made many seminal contributions in the field, beginning with work on (TEA) CO2 lasers and the photon-drag effect in semiconductors, measurement of the optical properties, including the absorption (at saturation levels), transmission and refraction of many semiconductor materials, two-photon absorption and carrier lifetimes. Maurice also carried out a great deal of work on far infrared detectors, including photon drag, HgCdTe and Schottky diodes. Among the sources he used, investigated or developed are CO2 lasers, p-Ge lasers, Smith–Purcell emitters, and last, but not least, free electron lasers (FELs), and he was particularly active in the latter field during the later years of his career at ENEA, Frascati.

Following his retirement from the University of Essex in the late 1980s, there was a remarkable renaissance in Maurice’s career when his services were sought out internationally as a research consultant and visiting professor in research laboratories around the world. These included appointments at the University of Buenos Aires, Dartmouth College in Hanover, New Hampshire, an Ivy League College, ENEA Frascati Research Centre, Rome (the Italian National Agency for New Technologies, Energy and Sustainable Economic Development), DLR, Berlin (the German National Aerospace Centre, and Heriot–Watt University, Edinburgh. Following the sudden tragic death of Professor John Walsh, Maurice’s colleague and collaborator at Dartmouth College in the late 1990s, leaving several graduate students stranded in the later stages of their PhD projects, Maurice spent several months in Dartmouth to support them through the final stages of their projects.

In 1998, DLR held a two-day symposium in Berlin in Maurice’s honour, and scientists came from all over the world to present papers as a tribute to him. The proceedings were published the following year in a special issue of the journal Infrared Physics and Technology. In the context of the International Series of Conferences on Infrared, Millimeter and Terahertz Waves, on the two occasions when the conference was held at the University of Essex in Colchester, Maurice was a member of the Local Organising Committee. He was awarded the Kenneth J. Button Prize for outstanding contributions to the science of the electromagnetic spectrum in 2004, and later served for a number of years on the Kenneth J. Button Prize Committee. In 2010, when the conference was held in Rome, Maurice was honoured by being appointed Honorary Chairman of the Conference.

Maurice will be greatly missed by members of the conference community, and we send our sincere condolences to his widow, Mhairi, who was well known in our community as she joined Maurice at many conferences as an accompanying person.

Terry J Parker January 24, 2020

Emeritus Professor of Physics

University of Essex

Colchester CO4 3SQ

UK

For a detailed professional biography on Professor Kimmitt please see:

2019

Akiyoshi Mitsuishi

Akiyoshi Mitsuishi was born on October 15, 1925, in Taejon, South Korea. He spent his childhood and early life in Taejon, and spent high school life in Hiroshima, Japan. Then he went to Kyoto to study at Kyoto University. He received an undergraduate degree in 1948. He continued his graduate studies at Kyoto University. During the period he was particularly affected by Prof. Uchida in spectroscopy and by Prof. Yukawa, the first Nobel Prize Winner of Japan in theoretical physics. Mitsuishi joined the research staff of Osaka University in 1940, where he mainly studied the optical properties of solids working in Prof. Yoshinaga’s laboratory. Akiyoshi contributed largely to the construction of the famous Far Infrared (FIR) grating spectrometer of Osaka University. His important role was to develop optical components such as the pile-of-plates polarizer, alkali halide powder filters (so-called Yoshinaga filters) and woven metal mesh reflection filters. Yoshinaga filters are particularly useful for suppressing the higher orders of the grating and useful as cooled filters for cooled detectors. At the initial stage of FIR spectroscopy by use of this grating spectrometer, Mitsuishi and collaborators applied it to the measurements of reststrahlen bands of well-known NaCl, KCl, and KBr, at 100 K, 200 K and 300 K. He and collaborators realized that NaCl has another subpeak and KBr has also a small subpeak on the sharp rise of short wavelength side (1959) in addition to the measured results in 1930. Charles Kittel included that data in a revision of his world-famous text book ‘Introduction to Solid State Physics’. This made Mitsuishi famous world-wide. In succession he pushed forward to the study of material science in solids such as color centers in alkali halides, phase change of ferroelectric crystals, shallow impurity levels of the doped semiconductor, and localized impurity modes. His scientific activities are written in Invited Review Articles of Journal of Infrared, Millimeter, and Terahertz Waves Vol. 35 (2014) and in Infrared and Millimeter Waves (ed. K. J. Button) 16, Chap. 6 (1986).

Akiyoshi was willing to support our communities which are not only domestic but international. He was the President of a large academic community Applied Physics in Japan and in succession was a member of the most powerful academic organization, the Science Council of Japan. He was the first president of The Japan Society of Infrared Science and Technology. Internationally he was an honorable advisor of the British journal Infrared Physics and the international advisor of the Chinese journal Infrared Research.

Akiyoshi supported our conference series working as the Local Committee Chair of the Takarazuka Conference in 1984, Vice Chair of the Sendai Conference in 1994 and Honorary Chair of the Otsu Conference in 2003. He was really a great scientist and a broad-minded person.

Akiyoshi Mitsuishi was awarded ‘The Order of the Sacred Treasure, Gold Rays with Neck Ribbon’ by the Emperor as a Great Professor.

Kiyomi Sakai October 4, 2020

Research Center for Development of Far-Infrared Region

University of Fukui

Fukui, Japan

Armand Hadni

We have just received the sad news of the passing of our friend and colleague, Professor Armand Hadni of the University of Nancy, France, on Monday, August 26, 2019, at the age of 94.

Armand Hadni was born on February 17, 1925, in Paris. He received his PhD in 1955 at the Sorbonne, where there is a long tradition in optics, and especially in the infrared. Alfred Kastler and Jean Lecomte, two giants in the field, were in the Jury. Armand went on to become one of the pioneers of far infrared spectroscopy of solids, founding the Laboratory for the Far Infrared at the University of Nancy, where he was appointed Professor of Physics at a very early age. His work was focussed in two main areas, instrumentation and solid state spectroscopy.

In instrumentation, Armand studied echelette gratings and developed a small grating interferometer for the far infrared. He went on to study the fundamental role of “étendue geometrique”, or “throughput” in English, which led him to Fourier transform spectroscopy and the development of new detectors such as germanium bolometers, pyroelectric detectors and a VIDICON tube with a pyroelectric retina which was produced commercially by THOMSON-CSF.

Armand used these techniques to study a variety of solids at temperatures from 4 K to 300 K. His samples included ferroelectric crystals and high Tc superconductors, and he obtained significant new results on ferroelectric soft mode behaviour and phase transitions, Debye relaxations, surface layers and electronic transitions. In work on high Tc superconductors, he obtained new results on plasma frequencies, collision frequencies and Bose–Einstein condensation, and he developed a new phenomenological model to calculate all infrared properties from 4 K to 300 K.

In 1967 Armand published the first comprehensive book in this field, “Essentials of Modern Physics applied to the Study of the Infrared”. This was a major undertaking by any standards, an authoritative review in English of the state of the art at the time extending to 725 pages and published by Pergamon Press. In 2002 he was awarded the Kenneth J. Button Prize for outstanding contributions to the science of the electromagnetic spectrum.

Armand was also very generous with his time in supporting our community. He supported our conference series from the very start in 1974 in Atlanta, Georgia, USA, and in 1983 he was Chairman of the Programme Committee and a member of the International Committee of the 7th International Conference on Infrared and Millimetre Waves in Marseille. He went on to serve for more than 25 years on various conference committees, including the International Organising Committee, the International Advisory Committee and the Prize Committee.

Armand Hadni was a gifted scientist and a wonderful person, and he will be greatly missed by his friends and colleagues around the world. We send our sincere condolences to his wife, Francoise, who joined Armand at many of our conferences as an accompanying person, and to the rest of his family.

Terry Parker August 31, 2019

T. J. Parker Emeritus Professor of Physics

University of Essex

Colchester CO4 3SQ

UK

Richard Pantell

Richard H. Pantell, Professor Emeritus of Electrical Engineering at Stanford University, died March 26, 2019, at the age of 91. Richard Pantell was an outstanding scientist of extremely broad interests and knowledge. He designed novel microwave and millimeter wave devices and made remarkable contributions to Free Electron Lasers (FEL) physics and technology, as well as to nonlinear optics and infrared lasers. Richard Pantell was born in New York City on December 25th, 1927. After completing his secondary education, he enrolled in Electrical Engineering at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, where he earned his bachelor’s and master’s degrees. He moved to Stanford in 1951, where he obtained his doctorate in 1954. He was then appointed assistant professor at Stanford and became full professor in 1964. In 1989, he became director of the multidisciplinary Ginzton Laboratory that included research groups from microwave engineering to laser physics and solid-state physics. He remained on the faculty until his retirement in 1994.

In the fifties, Richard Pantell joined the effort to develop high frequency microwave sources to reach the millimeter and submillimeter range overcoming the physical limitation in realizing resonant cavities at the fundamental frequency. This is testified by a number of high quality pioneering papers on resistive frequency multipliers, dielectric slow-wave structures, harmonic travelling wave tubes, backward wave oscillators, and the helical electron beam tube, which was a predecessor to electron cyclotron masers and gyrotrons.

With the advent of laser in 1960, Pantell and coworkers turned their attention and to the generation of sub-millimeter waves by optical methods. As early as 1962, Richard Pantell together with M. D. Domenico, J.R. Fontana and 0. Svelte published a method for generating submillimeter radiation by mixing of optical wavelengths. This method was successfully employed in single CdSe crystals and in other semiconductors. Pantell’s research on laser in the sixties covered external seeding, tunability of the Raman Laser mode coupling, nonlinear absorption. In the community of terahertz parametric generation, Pantell is known as the person who discovered the so-called Stimulated Polariton Scattering (SPS) in Lithium Niobate leading to the realization of a continuously tunable submillimeter waves source. In this period, he also co-authored with H.E. Puthoff a world-famous book on the fundamentals of Quantum Electronics.

In the seventies he started a new research line on the generation of Cerenkov radiation as a light source in the optical region and in the ultraviolet. He also turned his attention to X-ray and y-ray emission from channeled relativistic electrons and positrons, which led to outstanding experimental results. Energy exchange between free electrons and an electromagnetic field became a hot topic of research again after John Madey’s first operation of the FEL. In this field too, Pantell searched for new schemes of operation, developing and successfully testing the so-called Gas Loaded FEL. As early as 1979, he published the first paper on laser-driven linear acceleration of electrons. This seminal work, reviewed in his FEL-Prize talk in 1996, set the guidelines for the design of all laser-driven linear accelerators. In FEL physics and technology Pantell also introduced the concept of optical resonators with a hole on axis to allow both outcoupling and the passage of the electron beam, and the design of a solenoid derived wiggler, which was successfully tested on a compact Far-Infrared FEL in the nineties. In this period, the coherent spontaneous emission by a bunched electron beam in FELs was also investigated. Later, he turned his interest to X-ray optics, neutron physics in materials analysis and medical applications. We are deeply grateful to Dick for his knowledge, expertise and sense of humour he shared with all his coworkers, students and friends, as well as for his legacy as a precursor in the field of infrared, millimetre and terahertz waves.

G.P. Gallerano, Y.C. Huang, J. F. Lampin, K. Mizuno, G. Neil, G. Nusinovich,

J.F. Schmerge, R. Temkin, M. Thumm

September 2019

2015

T V George

Dr. T. V. George, a brilliant scientist, extraordinary leader of research on fusion energy and a wonderful friend to countless scientists in the international science community, passed away on May 10, 2015 after a long illness.

Dr. Thycodam Varkey George, known to everyone as T.V., was born in Kerala, India. He came to the United States for his graduate work, receiving the M. S. and Ph. D. degrees in Electrical Engineering from the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign. He served as a Professor at the Univ. Illinois before moving to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania to become a Senior Engineer at the Westinghouse Research Laboratory. There he became interested in the rapidly-growing field of plasma physics and nuclear fusion energy. He soon took a position at the US Department of Energy (DOE) in the Washington DC area, where he served for over thirty years as a program manager. Dr. George oversaw many different research programs, but he was particularly well-known nationally and internationally for his oversight of the development of gyrotron-based, high-power Electron Cyclotron Resonance plasma heating systems. Under his leadership, the US went from developing relatively low-frequency gyrotrons at power levels of one-two hundred kilowatts to achieving megawatt power levels at the high frequencies needed for modern plasma physics research. Dr. George also served as a Program manager for fusion experiments at all size scales, from the very large to smaller, innovative confinement experiments within the US Fusion Energy Sciences Program. He retired from DOE in 2010.

Dr. George was a champion of collaboration in scientific research. He was a key member of the International Organizing Committee of this Conference from 1997 to 2012. He initiated many international exchanges, including a series of Workshops on Electron Cyclotron Heating Technology that are held directly after this Conference. Dr. George organized countless collaboration meetings between the United States and Japan, Europe, and Russia. He was on the organizing committee of the bi-annual Shenzhen Conference in China. T. V. George and his wife Achamma were gracious hosts to many visitors to the Washington, DC area for more than three decades. An invitation to the George home was a very special and festive occasion. T. V. and Achamma also traveled throughout the world, making countless friends on every continent. T.V.’s wisdom, optimism and infectious good humor will be especially remembered by the IRMMW-THz community.

Dr. T. V. George is survived by his wife, Achamma, and their three children Asha, Shobha and Sageev (wife, Donell). IOC Members – 2015

2014

Hui-Chun Liu

Hui-Chun Liu was known for his groundbreaking work with semiconductor quantum devices, Hui-Chun Liu passed away on 23 October 2013, at age 53 in Shanghai, China; he had taken a bad fall and was in a coma the last nine days of his life. His sudden and unexpected death is a shock to the physics community.

Known to colleagues as H.C., he was born in Taiyuan, China, in 1960. He received his BSc in physics from Lanzhou University in 1982. After success-fully passing the selection process for the second-year China–US Physics Examination and Application program, H.C. went to the University of Pitts-burgh, where he received his PhD in applied physics in 1987 in the group of Daryl D. Coon. His major research interest was semiconductor nanoscience and quantum devices.

H.C. joined the Institute for Microstructural Sciences of the National Re-search Council Canada as a research associate in 1987 and rose rapidly through the ranks. In 1998 he was named to lead the council’s terahertz and imaging devices group and in 2000 he became a principal research officer – the highest rank, reserved for very few. In 2011 he returned to China to take a position at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, where as a chair professor he put together a new research group. H.C. had been recruited through the “1000 talents” program, which brings top-class minds to China from over-seas. He founded two high-tech companies in China: Debut Optoelectronic Sensors in Wuxi, and Ghopto Shanxi Guohui Optoelectronic Technology in Taiyuan.

Among H.C.’s honors were the Herzberg Medal from the Canadian Association of Physicists in 2000, the Bessel Prize from the Alexander von Humboldt Foundation in 2001, and the Jiangsu provincial high-level innovation-entrepreneur talent award in 2011. H.C. was granted more than a dozen patents, wrote or co-wrote more than 380 articles in refereed journals, and gave 95 invited presentations at international conferences. When H.C. was still in graduate school in the 1980s, the field of intersub-band transitions in semiconductor quantum wells was born. H. C. was one of the founders of the field of quantum well infrared photodetectors (QWIPs). As a junior researcher at National Research Council Canada, he started a world-leading re-search program on QWIPs. The ultrafast QWIP technologies he developed are being used in leading research laboratories and industries, including Harvard University, ETH-Zürich, and Northrop Grumman. His patented upconversion pixel-less im-agers have attracted considerable attention, as has his pioneering extension of QWIPs into the terahertz spectral region.

H.C.’s name has become synonymous with QWIP. He edited two volumes of the series Semiconductors and Semimetals and wrote a monograph on QWIPs. He served as chair or co-chair of various QWIP workshops, was twice chair of the International Conference on Intersubband Transitions in Quantum Wells, and was a member of several steering and advisory committees overseeing the strategic development of terahertz technology in China.

In addition to his laying the foundations for the field of QWIPs, H.C. demonstrated two-photon absorption in QWIPs, studied various nonlinear optical phenomena through intersubband transitions, and developed an intersubband Raman laser. Early in his career, he did innovative analysis on resonant tunneling di-odes. More recently, he was focusing on terahertz quantum cascade lasers and, with his collaborators, achieved a record-high operating temperature, which is significant, since increasing the lasers’ operating temperature is the most important challenge in the field.

H.C. was like a brother to many of his colleagues around the world. A unique leader, he was generous with and fiercely protective of his staff, was attentive to their well-being, and knew instinctively how to draw out the best skills of each team member. He instilled a sense of common purpose in all. His calm and positive demeanor greatly influenced his colleagues and especially his students.

H.C.’s unfailing support and loyalty will be deeply missed, and he will al-ways be fondly remembered.

Tucson, September 2014 Harald Schneider, Qing Hu, Emmanuel Dupont, Xi-Cheng Zhang, Chao Zhang, and Jun-Cheng Cao

Masanori Hangyo

The co-initiator and mentor of terahertz science and technology in Japan

Masanori Hangyo inspired research on terahertz (THz) science and technologies in Japan and led the THz community as a mentor of outstanding capability. Hangyo, who passed away in Osaka on October 25, 2014, was born in Toyama, Japan, in 1953 and spent his childhood and early life, up to his high school days, there. He then went to study at Kyoto University, and in 1976 received an undergraduate degree in physics. He continued his graduate studies at Kyoto University and completed his Ph.D. in 1981. After graduating from Kyoto University, Hangyo joined the research staff of Osaka University. He mainly studied the optical properties of solids there, working in Prof. A. Mitsuishi’s laboratory, which was known worldwide as a result of its spectroscopic studies on solid state materials in the far-infrared region.

Initially, Hangyo studied solids by using Raman spectroscopy. But later, he and his colleagues started studying solid materials by using far-infrared spectroscopy. They constructed a dispersive interferometer for the mm and sub-mm region consisting of a Calcinotron and multipliers as the radiation source, and a Mach-Zehnder interferometer. By using this spectrometer, Hangyo was able to measure the optical properties of some solid materials. These experiments were rather time consuming and demanding, but in 1988, he came to know of Terahertz Time Domain Spectroscopy (THz-TDS), learning about it from Dr. Sakai who excitedly told Hangyo about the THz-TDS technique reported at the IRMMW Conference that year.